quaqua sprrtzz popo

jkktvzdn prpp tsff

grd grdd grdddd dd

I'm betting that most of you just read those words in order, first line first, then the second, etc. Maybe you gave up long before that final "dd" (and wouldn't you agree it was such a magnificently subtle, understated chord on which to end?), realizing it was pure nonsense. Even so, you did begin, automatically, to scan those four lines as if they were regular text, intended to be read in a regular fashion, left to right then top to bottom.

On the other hand, if you just saw type specimens such as these:

you would immediately know that they are just disconnected letters, not intended to be scanned as reading, and you would be just content to look at the picture. Which is to say that, when looking at letters, knowing when to read or not to read, when to scan or not to scan, is all a matter of context and of learned habits.

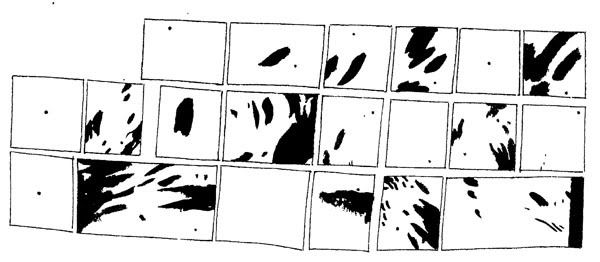

Which leads me to abstract comics. Now, abstract comics, obviously, do not have a (verbal, summarizable) plot to push the narrative forward, one that would automatically prompt the reader to go to the next panel, and the next, and the next. They make up for it in a variety of ways. They can show shapes recurring and slowly changing from panel to panel, as in this excerpt from Warren Craghead:

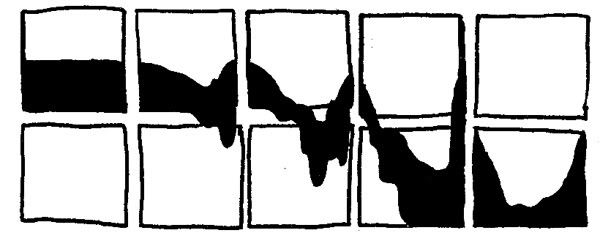

They can rely on the continuity of an image across panels, while modulating the continuing shape to lead the eye downward and to the right, as in these two (?) tiers from Ibn al Rabin:

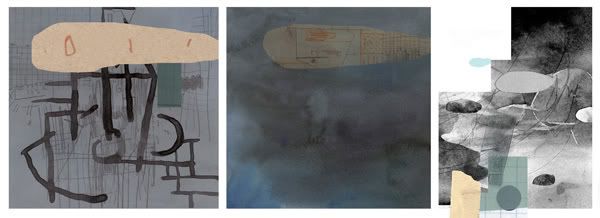

Or they can rely on the sheer energy of the compositional vectors in each panel to move the reader's eye sequentially (or at least to give it the feeling of sequential drive, even if we may not stop to examine one panel at a time), as in these three tiers from a piece by Benoit Joly:

(All excerpts, by the way, are taken from pieces in the anthology.)

The variety of ways in which abstract comics can create sequence and panel-to-panel scanning even in the absence of story and plot still needs to be cataloged, and is certainly much much wider than the three possibilities I have posted here. Each successful comic does this in some way. If it does not do so from panel to panel, it may do it from page to page, as happens in a couple of examples in the anthology. Yet, even in the absence of any such signifiers of movement or of sequence, I think that--as with the nonsense words above--the very fact of images presented in panels, in a comics context, will at least give us a first impulse toward sequentiality. On the other hand--and similarly to the type specimens above--in a non-comics context, such as a gallery wall or a piece of fabric, such an image, if it has no further forces to guide the viewer's eye, will most likely not invite a sequential reading, but simply appear as, say, a patchwork of rectangles. Context is all, or at least a lot. We are practiced readers of comics, after all. We know how these gizmos are supposed to work. And I would suggest that that is the very first of our tools, the foundation upon which we can begin to build any more satisfying abstract sequences.